This will be the first post of my substack that I primarily created to do longer posts outside of the platform formerly known as Twitter.

In just a few days, Russia and Iran are set to sign the long-anticipated Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Treaty - a milestone considering how far this relationship has come. Before diving into what this new agreement means, I wanted to take a step back and look at its predecessor - the 2001 Treaty on Mutual Relations - and reflect on how far things have come. Having spent more time than I care to admit studying Russia-Iran relations, I would like to go back to a period of time that is sometimes forgotten in the current discourse by ‘experts’ who pen articles on the so-called 'Axis of [insert word implying danger].’ In 2001, the level of cooperation between Russia and Iran that we see today would have been unthinkable. But, alas, here we are.

Let’s begin in March 1993 when former Russian Foreign Minister Andrey Kozyrev visited Iran to meet with his counterpart Ali Akbar Velayati. A key issue at the meeting was the ongoing civil war in Tajikistan. Russia was increasingly frustrated with Iran’s alleged support for the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, a political movement with Islamist leanings that was part of the opposition forces in the civil war. This support, from Moscow’s perspective, violated the 1989 agreement between Iranian President Rafsanjani and Soviet leader Gorbachev, which emphasized non-interference in each other’s internal affairs. Moscow viewed Iran’s involvement in Tajikistan as a direct threat to its interests in the so-called near abroad but Russian policymakers were also worried about the spread of Islamic Fundamentalism. Iran eventually relented and pulled back much of its support, though the civil war in Tajikistan is a topic for an entirely different post.

So why was this meeting important for the 2001 Treaty? Since September 1992, both sides had been engaged in negotiations aimed at formalizing their relationship with a treaty (Iran had hoped for a strategic partnership but the Russians had little interest in that). So in March 1993, when Kozyrev and Velayati met in Tehran, both sides aimed to initial the draft agreement. This happened. The document was intended to serve as a precursor to a high-level summit between Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. However, that much-anticipated summit never took place.

Fast forward to 2001. Putin is in his early years of the presidency. Russia, still irked by the 1999 Kosovo crisis, saw Iran as a potential counterbalance to the West. Even back then, there were frustrations about U.S. policy. And, of course, the Russians saw Iran as a potential partner to express this discontent.

In 1997, Mohammad Khatami - an ostensible reformist who accomplished little reform - was elected president. The Iranians continued to push for a high-level summit and for an agreement that would codify the expansion of ties. The summit would happen but the treaty would fall short of Iranian expectations.

Eight years after Kozyrev visited Iran to initial the treaty, the Iranians got their long-anticipated summit. In March 2001, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Mohammad Khatami met in Moscow to sign a treaty that had been nearly a decade in the making: Treaty on the Basis for Mutual Relations and the Principles of Cooperation between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Russian Federation. For the Iranians, the actual content of the treaty fell short in multiple areas - most notably the level of commitment in instances of aggression against either party. Rather than breaking new ground, it provided a framework for cooperation that remained vague and, to Iran’s dismay, avoided any mention of ‘strategic partnership.’ At the heart of this restraint was Russia’s reluctance to make any firm military or strategic commitments to Iran. The 2001 treaty did not pledge mutual military support in the event of aggression. Instead, it merely stipulated that neither side would assist an aggressor in case of attack, and that both would seek a peaceful settlement of disputes in accordance with the UN Charter and international law. This was a crucial point—while Russia was willing to foster closer ties with Iran, it was careful to avoid any military entanglements that could jeopardize its relations with the West, particularly with the United States.

The absence of any binding military-political commitments in the treaty reflected the broader dynamics at play in Russian foreign policy at the time. Putin, who had only been in power for a year, was still navigating Russia’s complex relationship with the U.S. and Europe. The Kremlin was keen to rebuild Russia’s economy, which had suffered in the 1990s, and saw engagement with the West as a necessary component of this recovery. The War on Terror which broke out several months after the Putin-Khatami summit also led Russia to prioritize ties with the US over Iran. Then, of course, Iran’s nuclear issue became front and center shortly after. Although Moscow and Tehran shared grievances about U.S. dominance in global affairs (even expressed back then), Russia was not ready to fully align itself with Iran at the expense of its broader diplomatic objectives.

Without going fully into the treaty, here’s a breakdown of what it covered:

Article 1: Both Russia and Iran agree to base their relations on sovereign equality, mutual trust, respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, and non-interference in internal affairs. (typical of almost all treaties)

Article 2: Both parties pledge not to use force or threaten to use force against each other and not to allow their territories to be used for aggressive or separatist activities against the other state. (weaker than what Iran wanted)

Article 3: If one party is subjected to aggression, the other party will not support the aggressor and will instead promote peaceful resolution of the conflict according to the UN Charter. This article reinforces mutual defense without direct military obligations. (weaker than what Iran wanted)

Article 4: The two states agree to resolve any disputes between them solely by peaceful means, affirming their commitment to diplomatic resolution and avoiding conflict escalation. (similar to other treaties by the Russians)

Article 5: Both countries commit to creating favorable conditions for bilateral and multilateral economic activities and joint investments, granting most-favored-nation status in trade and enhancing economic cooperation through a Russian-Iranian commission.

Article 6: The treaty emphasizes cooperation in long-term and mutually beneficial projects in transport, energy (including nuclear energy for peaceful purposes), industry, science, agriculture, and healthcare. (basis for the Bushehr nuclear power plant)

Article 7: Regular consultations and exchanges of information and experience in economic and scientific areas are promised to enhance mutual potential. (somewhat ironic since much of the science cooperation previously came from rogue Russian actors operating outside of Yeltsin’s purview, though Putin would crack down on this)

Article 8: The parties will strengthen people-to-people connections through interaction between public organizations, religious groups, youth, and women’s associations. Simplifying visa procedures for citizens involved in tourism, trade, science, and culture is also prioritized. (separate agreements came from this)

Article 9: The two nations will promote cooperation in cultural, scientific, educational, artistic, and sports fields. They will encourage direct contacts between institutions and foster mutual understanding, including the promotion of Russian language in Iran and Persian in Russia. (much more of an effort now to promote this)

Article 10: The treaty provides for the conclusion of separate agreements to define the specific areas and scope of cooperation, ensuring flexibility and adaptability in future partnerships.

Article 11: Russia and Iran will enhance inter-parliamentary relations, including strengthening ties between parliamentary friendship groups. (basis for Russia-Iran interparliamentary commisions)

Article 12: Regarding cooperation in the Caspian Sea, the parties recognize earlier treaties (1921 and 1940) as the legal foundation and agree to further develop mechanisms for cooperation in fishing, shipping, trade, resource development, and environmental protection, pending the clarification of the Caspian's legal regime. (don’t get me started on the Caspian)

Article 13: The treaty emphasizes regional cooperation, utilizing their respective capacities in areas such as transport and energy.

Article 14: Regular consultations on bilateral relations and multilateral cooperation will take place at various levels. In the event of a situation threatening peace or security, the parties will immediately consult on measures for resolution.

Article 15: The parties aim to strengthen the UN’s role as a universal mechanism for peace and security and to deepen their cooperation within the UN and other international organizations, showcasing their global cooperation strategy. (a lot more of this in the future)

Article 16: Russia and Iran will collaborate on disarmament, reducing and eliminating weapons of mass destruction. Regular consultations will ensure coordination in international security, non-proliferation, and export controls. (a Russian effort to assuage US concerns)

Article 17: The parties will cooperate on environmental protection, sharing experiences in the sustainable use of natural resources, promoting eco-friendly technologies, and helping each other prevent and respond to natural disasters.

Article 18: Bilateral and multilateral efforts to combat terrorism, hostage-taking, crime, drug trafficking, arms smuggling, and the illicit trade of historical and cultural goods will be a focus of security cooperation. (separate agreements came from this)

Article 19: The treaty affirms both countries' commitment to fighting all forms of racism and racial discrimination, emphasizing the importance of ethnic and religious harmony and protecting the rights of national groups and religious communities. (this would evolve into their civilizational rhetoric)

Article 20: The treaty does not affect the parties' rights and obligations arising from other bilateral and multilateral agreements, maintaining the integrity of their existing international commitments.

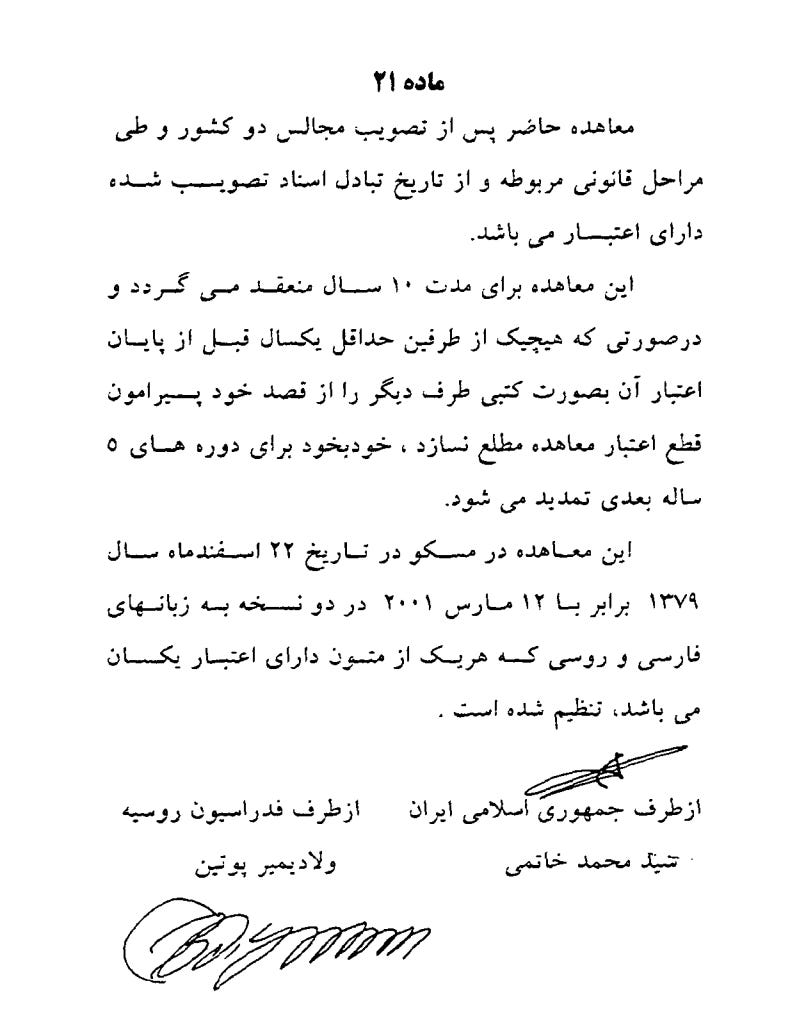

Article 21: The treaty is subject to ratification, with an initial term of 10 years, automatically renewable in five-year increments unless one party gives written notice of its intention to terminate it at least one year before the end of the current term.

A little more than two decades later, Russia is now eager to have Iran as a strategic partner. Tomorrow, I will write about what I think will be in the Treaty on Strategic Partnership and how we got here.